Why the Qur'an might not be what you thought, and why it matters

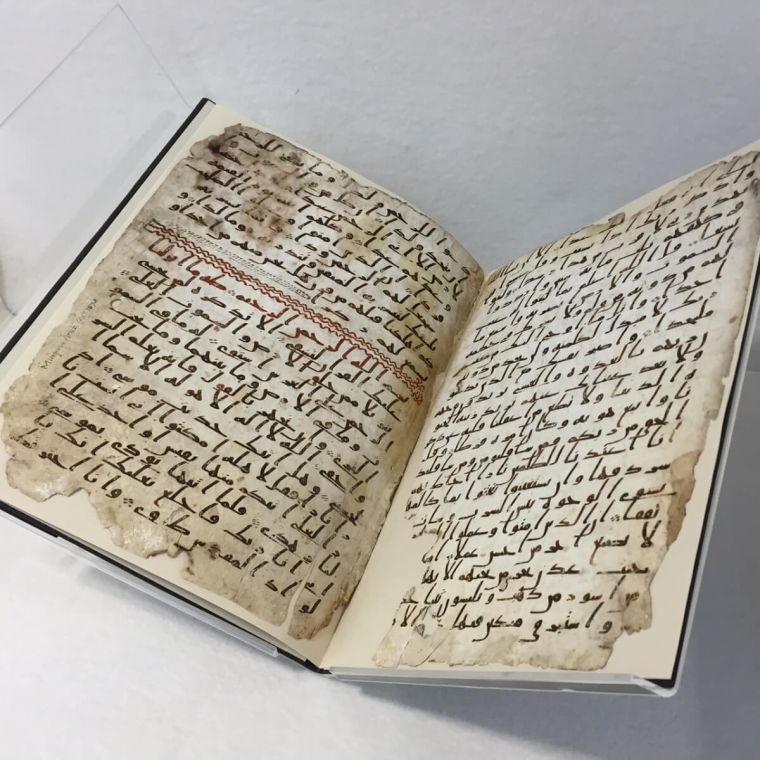

On the face of it, it's a little unlikely. But not long ago, what may be the oldest copy of part of the Qur'an was discovered in the Cadbury Library at Birmingham University.

The two parchment leaves had been bound together with leaves of a similar Qur'an manuscript, which is datable to the late seventh century. These, however, are earlier. Radiocarbon analysis has dated the parchment – prepared animal skin – on which the text is written to the period between AD 568 and 645. Mohammad himself is generally thought to have lived between AD 570 and 632, raising the intriguing possibility that it could have been written in his own lifetime.

The fragment contains parts of suras (chapters) 18-20, written with ink in an early form of Arabic script known as Hijazi. So far, so fascinating: it's like finding a copy of one of Paul's letters from 40 AD, or a Matthew's Gospel from 80AD. From a historical point of view, it sends goose-bumps up the spine – and for a Muslim, even more so. The chairman of Birmingham Central Mosque is reported to have said: "When I saw these pages I was very moved. There were tears of joy and emotion in my eyes. And I'm sure people from all over the UK will come to Birmingham to have a glimpse of these pages."

But does it have any more significance than that?

In many ways, far more interesting is the way it highlights Islamic origins – and the attitude of Muslims to the Qur'an today, which is fundamentally different from the attitude of Christians to the Bible.

During the last 200 years, most Christians have got used to the idea that as well as being an inspired text, the biblical writings were produced by human beings. They were shaped by human experience, and learning about their context is vital if we're to understand them properly. They've also been transmitted through a complicated process of copying and recopying, many existing in hundreds of slightly different versions. Most of us are happy to recognise that there are some contradictions within its pages – like the two different accounts of the death of Judas – and it doesn't particularly worry us. For most Christians, biblical criticism isn't threatening at all; reverently and humbly undertaken, it enriches our understanding of the word of God.

The Qur'an is different – and the Muslim view of the Qur'an is different.

In Muslim tradition, the Qur'an was personally revealed to Mohammad, beginning in 610 AD and ending with his death in 632 AD.

Muslims believe that Mohammad was simply a messenger. The Qur'an does not reflect his personality; he had no influence on the text at all.

Mohammad himself was illiterate. The revelations were given to him by the angel Gabriel and were purely verbal, learned word-for-word by the prophet's followers and passed on through oral transmission. This doesn't mean it was inaccurate, as the people of the time had developed remarkable powers of memory for poetry and stories.

After Mohammad died, the separate revelations were brought together. In Sunni tradition this was after the battle of Yamama in 633, during which many who had memorised the texts died. His primary scribe was tasked with collecting them and found them written down on parchments, the shoulder blades of camels and palm leaves, as well as memorised by disciples.

The Qur'an's text was fixed under the third caliph, Uthman ibn Affan (576-656) about 20 years after the death of the Mohammad. Uthman had a standard version compiled and all other copies were destroyed. There are very few variations in the Qur'an as it's known today, and none of any significance.

All of these means that for Muslims to approach the text of the Qur'an in the same way as biblical scholars might approach the Bible is unthinkable. Most of the critical work on the text, such as it is, has been done by Western non-Muslim scholars rather than by Muslims.

Sceptics point out the holes in the traditional account of the written Qur'an's creation by Uthman. He is said to have created four or five copies, regarded as the perfect copies by which all others are judged. But what happened to them? There is an 'Uthman Qur'an' in the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul, but it is known to be slightly later than his period. There is no record of the fate of any of the originals – and if they had been lost or destroyed this would surely have been recorded.

Whatever happened to the Uthman Qur'ans, for many scholars the idea that such wide-ranging and complex ideas could simply come out of nowhere and emerge fully-formed in the mind of an illiterate Arab tribesman stretches credibility too far. Perhaps there were earlier religious traditions on which Mohammad drew – maybe in Persia? Perhaps there were even pre-existing texts and not everything preserved as Qur'anic was in fact from Mohammad. And what was lost when Uthman harmonised the Qur'anic writings, and what would it tell us about the origins of Islam?

It may be impossible to say. One Western scholar, Keith Small – who lectures at the London School of Theology and the Oxford Centre for Christian Apologetics – argues in his book Textual Criticism and Qur'ān Manuscripts that it's impossible to construct a critical text of the Qur'an because there aren't enough separate sources, thanks to Uthman.

These are the sorts of questions that are likely to occur to scholars educated in the Western tradition of radical doubt. They aren't questions that would occur as a matter of course to Muslim scholars, unless a demonstrably pre-Islamic text containing verses from the Qur'an turns up in a jar in a desert cave – and certainly not to Muslim believers in the average UK mosque, for whom the transmission of the Qur'an is absolutely perfect.

Does it, in the end, matter very much?

At one level, no. At a theoretical level, it might be argued that it's harder for Muslims to ignore verses in the Qur'an which seem to approve of abhorrent practices like sex slavery or violence. There are plenty of these in the Bible, too – Leviticus 21:9 commands that the daughter of a priest who becomes a prostitute shall be burned alive. Neither Christians nor Jews regard themselves as bound by this today. The brutal zealots of Islamic State appeal directly to them to justify their practices, but they are the exception to the rule: most Muslims fit in with modern society perfectly happily, and would regard such barbarity with the same horror as the average Anglican.

In practice, most Muslims manage to negotiate their scriptures, as most Christians do. Many argue that commands which seem to advocate practices like stoning adulteresses or cutting the hands off themes have been misinterpreted. Others say the political situation has changed and that these commands don't apply.

There is, however a pressure point. The Muslim veneration for Qur'an is of a different kind than the Christian's for the Bible. So an insult offered to the Qur'an – by burning or otherwise destroying it, for instance – is felt at a far deeper level. It is not seen as a record of the word of God, delivered through human hands and brains; it is far purer and more immediate than that.

And the figure of Mohammad, because he was the pure vessel in which the Qur'an was contained – as the Virgin Mary was the vessel for the Incarnation – is seen differently from Christ. His person is inviolable and an insult to him is an insult to God. So there is outrage, pain and resentment.

For Christians, Christ is the Son of God, the second person of the Trinity, of one substance with the Father and the Spirit. We venerate him more, rather than less. But at the heart of the Christian story is his crucifixion and death. To see him mocked and abused, as he often is in our irreligious Western world, is sometimes very painful, but we don't think of retaliating or taking it personally. Christ came to suffer and to die. If he is mocked and insulted today, it's just more of the same. He can take it.

So it may be that the Christian understanding of the Bible lets us fit more easily into today's world than the Muslim understanding of the Qur'an. A deeper awareness of each others' tradition, though, can only be a good thing.

Follow @RevMarkWoods on Twitter.