Will Sir Keir apologise to the Windrush generation?

The 'Windrush generation' became a short-hand media term for a tragedy in government policy that destroyed the lives of hundreds of British citizens from the Caribbean. The scandal that came to light in 2018 saw people who had lived, worked, and paid taxes in the UK for decades wrongly detained and threatened with deportation. Many have died in the ensuing three years without receiving the compensation that the government promised would be given speedily.

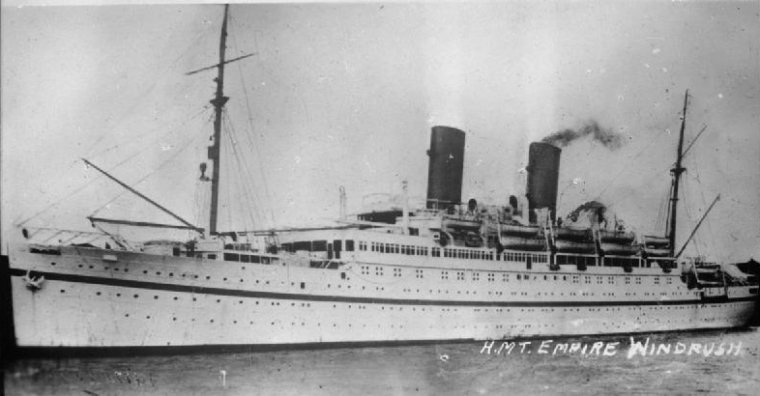

The Windrush generation refers to the many people who arrived in the UK from Caribbean countries between 1948 and 1971. The name is taken from the MV Empire Windrush, which left Jamaica on 24 May 1948 (Empire Day) and finally arrived at Tilbury on 22 June with its 492 predominantly Jamaican passengers hoping for a new life in the 'mother country'.

Today we remember those who arrived in the UK seeking a better life for themselves and their families. The passenger records indicate that although the majority of those on board the Empire Windrush came from Jamaica, there were also a significant number from Trinidad, the Bahamas, and Guyana. There were many young people on board; some with places to stay on arrival (at least that is what was recorded in respect of the official 'Proposed Address in the United Kingdom').

Lucy Barrow was 19-years-old and registered as a student in the 'Profession, Occupation, or Calling of Passengers' in the ship's log. Fortunately for Lucy, she intended to reside at 45 Manor Lane, Lewisham, London, SE13. Similarly, the young 21-year-old machinist, George Richardson, was hoping to settle in Liverpool. Unfortunately, for both Bertram Springer the cabinet maker and Clive Winston the clerk (both aged 19), they had no 'proposed address'.

Around 240 of those who fell into this category were put up in the Clapham South Underground shelter, a windowless temporary accommodation under the tube station.

A tale of service to the 'mother country'

The experience of Alford Gardner and Sam King is typical of many of that generation. Those on the Empire Windrush came to the 'Mother Country' with hope in their eyes. In the Caribbean, they had studied the language, history, geography, and customs of Britain. Many of them, like these two men, had contributed to the war effort by joining the Armed Forces.

Alford was born in Jamaica on 27 January 1926, one of 10 children. Like so many Caribbeans, he answered the call for help from the 'Mother Country' during the Second World War. At age 17, he joined the RAF as a motor mechanic engineer and arrived in England in 1944. Alford completed his initial training in Staffordshire and was later posted to Moreton-in-Marsh in Gloucestershire. His certificate of discharge states that his general character during service and on discharge was 'very good', and that his work as a mechanic was 'above average'. Before Alford went back to Jamaica after the war, he completed a six-month engineering vocational course in Leeds.

He was back in Jamaica 'in time for Christmas' in December 1947, but like another RAF man from Jamaica, Sam King, Alford bought his £28 ticket for his place on the SS Empire Windrush to return to Britain.

Sam King tells us in his autobiography, Climbing Up The Rough Side of The Mountain, that the people he met on the Windrush 'were optimistic, adventurous and creative'. He goes on to say that one 'would not have thought they were bound for a strange land'. However, their peace and optimism, says King, 'abruptly came to an end' when there was news of the consternation in the House of Commons when MPs were informed of the numbers of immigrants on board 'and that the ship had been ordered to turn back'.

Unsurprisingly, King relates the 'distress' and despondency of the passengers. Indeed, he tells us that many were forlorn and overcome with grief. According to him, one man 'cried like a baby'. To make things worse for these Caribbean pioneers, the stern and inflexible voice of the Welfare Officer from the Colonial Office struck discouragement and fear into 'the already distraught passengers' with the message he had typed, distributed, and pinned up on the notice board. According to King, the message which drove 'the last nail in the coffin', read:

'I could not honestly paint a very rosy picture of your future; conditions in England are not as favourable as you may think. Various reports you have heard about shortage of labour is not general. Unless you are highly skilled, your chances of finding a job are none too good. Hard work [as if we didn't know] is the order of the day in Britain, and if you think you cannot pull your weight you might as well decide to return to Jamaica, even if you have to swim the Atlantic.'

Not exactly encouraging or endearing words from the Welfare Officer, you might say. But more discouraging words and sentiments were yet to come - and in quick succession, this time from Labour MPs. It was to be a portent of the struggles the Caribbean community would have to endure for decades to come.

The 11 Wise Men of Westminster

The day the Windrush arrived, the London Evening Standard carried the headline 'Welcome Home', a positive message to the newcomers. The film crew from Pathé News managed to get the Trinidadian calypso singer Lord Kitchener (Aldwyn Roberts) to give a rendition of his new song 'London is the Place to Be'. However, on the same day 11 Labour MPs led by J.D. Murray wrote to Prime Minister Clement Attlee complaining bitterly about the 'discord and unhappiness' this wave of Caribbean immigrants would cause.

The letter stated:

Dear Prime Minister,

May we bring to your notice the fact that several hundreds of West Indians have

arrived in this country trusting that our Government will provide them with food,

shelter, employment and social services, and enable them to become domiciled

here...Their success may encourage other British subjects to imitate their example

and this country may become an open reception centre for immigrants not selected

in respect to health, education, training, character, customs...The British people

fortunately enjoy a profound unity without uniformity in their way of life, and are

blest by the absence of a colour racial problem. An influx of coloured people

domiciled here is likely to impair the harmony, strength and cohesion of our public

and social life and to cause discord and unhappiness among all concerned.

Although two-thirds of the passengers on the Windrush were ex-servicemen who fought for Britain ('for King and Country') during the Second World War, these Labour MPs felt that in peace time, post-war Britain, people like these from the Caribbean were totally unsuited to settle in the very 'Mother Country' they had recently fought for.

Undoubtedly, the Labour MPs displayed the type of prejudice and fear that would set the tone for the discrimination and struggles that the Caribbean community would subsequently face.

One can only imagine how ex-servicemen like Sam King and Alford Gardner would have felt to be told that they were unsuited by their 'education, training, character' to settle in Britain; or that their presence would fracture the nation's harmony, cohesion and happiness. In short, the message to them was unambiguous: their domicility in Britain foreshadowed 'colour racial problems', the likes of which had hitherto been absent in the country. And all this was before the brutal murder of Kelso Cochrane in May 1959 by a group of white youths in Notting Hill Gate and Enoch Powell's 'rivers of blood' speech in April 1968.

Last year, in the General Synod of the Church of England, Archbishop Justin Welby apologized to the Windrush generation and Black Anglicans for their poor treatment by the Church, with the Archbishop actually saying that the Church was 'institutionally racist').

On this third anniversary of National Windrush Day honouring Britain's Caribbean community, it's time for Sir Keir Starmer, Leader of Her Majesty's Opposition, to apologize to the Windrush generation for that shameful and scandalous letter that members of his party wrote to Attlee on 22 June 1948, the hurt from which is still very much felt today.

Dr R David Muir is Head of Whitelands College, University of Roehampton, and Senior Lecturer in Public Theology & Community Engagement. He is the Director of the Centre for Pentecostalism & Community Engagement at Roehampton and executive member of the Transatlantic Roundtable on Religion and Race (TRRR). In 2015, he co-authored the first Black Church political manifesto, produced by the National Church Leaders Forum (NCLF).